The legacy of Noord presents us with a powerful symbol of the social democratic dream of elevating and ‘civilizing’ the working class to middle class norms. But today, with the strategic shift from heavy industries to creative industries, we are witnessing an altogether different development. The focus on the local population has given way to effervescent marketing strategies trying to import a new middle class, rather than elevating the existent population. As I will argue in this presentation, what we are witnessing is a change in governing strategy, which is shifting from social engineering to spatial engineering.

Social Engineering

In his book Discipline and Punish (1975) the French philosopher Michel Foucault argues that the idea of social engineering enjoyed great momentum in the nineteenth century, when governments started to develop all sorest of controlling techniques, aimed at constraining the unruly working class. There are two sides to this coin: on one side it involved the idea of emancipation and edification, on the other the element of control, of discipline and surveillance. Social engineering refers to efforts to influence popular attitudes and social behaviors on a large scale. In Dutch it forms part of the concept of "maakbaarheid", construction: the idea that, by human intervention, society can be given a definite shape. The social variant of maakbaarheid is the idea that man – just like the Dutch landscape – can be moulded, that a new man can be made from existing, dysfunctional material. From the early twentieth century, Amsterdam Noord was one of the laboratories of social engineering in The Netherlands. An extreme example of this civilizing offensive was the social re-education camp called Asterdorp.

With the rise to power of the social democrat party in the beginning of the 20th century, an extensive administrative machine was set up with the aim of uplifting and civilizing the working class. Central to this program was the teaching of middle class faculties such as devotion to duty, self constraint, the saving of money, and the development of a proper work ethic. It was thought that through the provision of welfare, such as housing or financial support, new morals could be imposed, by threat of withdrawal of the given support (Dercksen & Verplanke, 1987).

At the very beginning of the twentieth century, growing concerns about hygiene and urban epidemics led to the policies of slum clearance in poor working-class neighborhoods such as the Jordaan, Uilenburg or Oostelijke Eilanden. An extensive program of public housing provision was set up, of which Amsterdam Noord is still a prima example. Besides the social ideals behind the program, it also had an explicit economic aim, in creating a compliant, cheap and efficient workforce. I quote from one of the first housing corporations:

“The houses are only to be rent out to neat people. There has to be strict supervision on the regular payment of rent. Showing weakness will lead to lazyness, and the goal of proper housing is promoting a good work ethic.” (quoted in Ottens, 1975, p5)

Problems soon arose with the former slum dwellers, who turned out not to be the neat people everyone thought they'd be. Tenants who couldn't pay their rent, did not maintain their houses properly or caused trouble for their neighbors, were immediately evacuated. To prevent further incidents, an extensive administrative system was set up to review new tenants for public housing. Superintendents would inspect the houses of families applying for public housing, checking each and every detail of their household and requiring information from employers, landlords, police etc. Between 1926 and 1938, 56.692 of these reports were made. From these families, 1292 were declared anti-social and “inadmissible”. In other words: unfit for public housing (Dijk & Steinmetz 1983).

Grotere kaart weergeven

A solution for the 'inadmissible' was found in the re-socialization camps, of which two were planned in Amsterdam. Zeeburgerdorp opened in 1926, and Asterdorp in 1927. The camps were built in isolated areas of the city, with the explicit aim of setting the inhabitants apart from the rest of the population. Director of the woningdienst Arie Keppler was personally in charge of the public housing development. He stated:

“In such an institution what is firstly needed is discipline, a discipline that imposed from the outside through the skilled and tactical behaviour of the superintendent, slowly proceeds to an inner discipline, as a consequence of the change in being and thinking of the people conferred to her.” (quoted in Dercksen & Verplanke, 1987, p44)

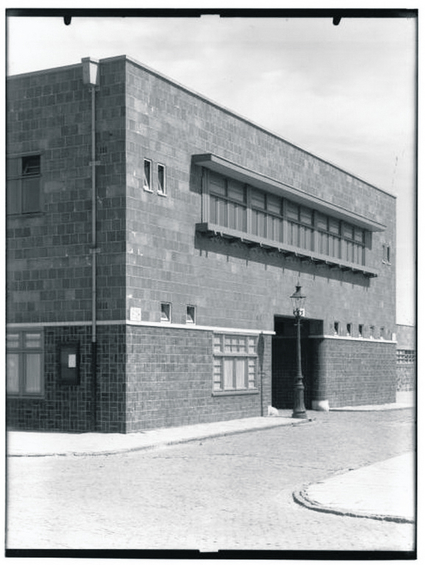

Asterdorp was comprised of 132 houses, built as a pentagon, surrounded by a 2,20 meters high wall. The only way to access the terrain was through the gate, which, although it was open, was supervised by the superintendent. She came to collect the rent every week, which was also occasion for a house inspection: she checked the wardrobe, the bed, the clothing, whether the kids were well fed and going to school, whether boys and girls of a certain age were sleeping in separate beds, etc etc. She kept a register of whether people were taking their weekly baths, and whether the women were doing their laundry. People were not supposed to linger and socialize outside, which was considered unfitting of modern family life. If the family’s problems were considered to be amendable, they could apply for re-entry into the public housing administration. But very few people were admitted.

Living in Asterdorp meant being imbued with a stigma. The kids were sent to school with red bands around their arms, a signal of their bad upbringing. If men even mentioned the name Asterdorp, they had trouble finding work or alternative housing. On top of that, the houses were suffering from moisture and were generally of poor quality. As a consequence, anyone that was strong and independent enough to leave Asterdorp left as soon as they could. Only the most problematic families stayed behind. In 1940, when WWII started, the institution lost its function. After and during the war it was used as various temporary forms of shelter. Finally it was demolished.

To conclude, Asterdorp is a profoundly interesting and powerful symbol of social engineering, the dream that a social body that can be formed and constructed by governments and middle classes. Even though it failed at assimilating the abnormal, it tells us a lot about social codes which were less tangible and explicit in the rest of society, but therefore no less powerful.

Spatial engineering

Whereas social engineering takes the given population of a city as its starting point, spatial engineering considers the location its point of departure. Branding and marketing strategies are used to attract new residents, in order to regenerate the location. Compared to social engineering, it's a reversal of means and goals - social engineers used the location to elevate its residents, whereas spatial engineers lure new residents to elevate a location.

In Amsterdam it was the appointment of social-democrat leader Van Thijn in 1983 that initiated the shift to market-led city politics. A branding campaign was launched with the slogan Amsterdam heeft 't (Amsterdam's got it). In the years to come, policy targets gradually shifted from population to location, in this case to Amsterdam as brand. A more recent example of the consequences of this shift, is a 2002 report on the housing market by the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce, which argued that in order to retain its competitive edge as a location, Amsterdam needed a better educated population and should, where possible, rid the city of the less-educated. In 2004, the city council published a report Ruimte voor Talent (Space for Talent), which delivered the same message in slightly more guarded terms.

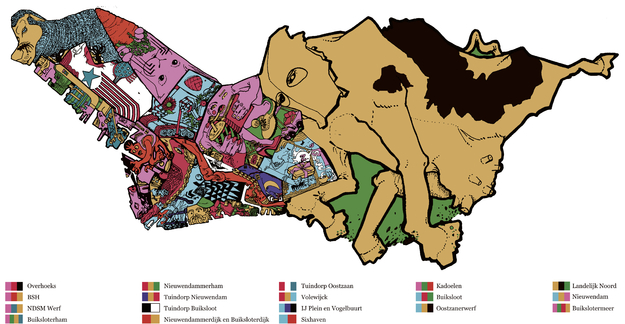

As we speak, a similar strategy of spatial mobility is pursued in Noord. Focusing on the creative industry, the new developments are primarily focused on creating employment opportunities for a new, highly educated and financially strong crowd. For most Noord residents the nine thousand homes currently being built in the area are almost all unaffordable. So while officially the plan is to bring Noord closer to the IJ, it would be more accurate to say Amsterdam city center is colonizing the northern IJ-bank. Residential and commercial areas are popping up along the IJ-bank causing a considerable degree of segregation between this are and the rest of Noord. Or in the words of the 2009 Noord Housing Vision: The combination of old, familiar neighborhoods and the new quarters creates a rare contrast in living experience. Social engineering is not just aimed at attracting talent, but also has as goal the removing of 'problems'. By means of large scale demolishment and regeneration, Amsterdam is attempting to create a new social make-up in its northern borough. The problem of social engineering has been coined the water bed effect: rather than disappear, 'problems' tend to resurface elsewhere.

The only alternative seems to be to return to the core of social engineering, and let residents rather than locations define policy. You can shuffle the cards all you want, but eventually you'll have to play with the cards you were dealt.

(This is a translated summary of an article that appeared in Dutch in: Huib van der Werf (ed.), Waterfront Visies. Transformaties in Amsterdam-Noord. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2009.)