The tradition of floral emblems is ancient. In some ways, such is counterintuitive, as flowers form an antithesis to nations and their borders to the extent that they are natural, organic features— but this quality has been precisely used to naturalize and personalize the arbitrarily marked pieces of lands (check our blog post about artist Minji Choi’s works confronting the idea of nativeness of botanical species for further exploration of this idea). Towards the end of World War I, Albert Hansen, American botanical scientist, urges that his nation is “in yearning need of sentiment”, in need of a floral emblem that celebrates those who return and consoles the souls of those who could not. He delineates the following aspects that a national flower ought to satisfy:

- Not a weed, or a pest, in any sense of the word– “A plant symbolic of our national flory should not be one that pesters and troubles the farmer”

- Native and common all throughout the country

- Easy to cultivate all throughout the country

- Aesthetically pleasing for both flower and the leaf

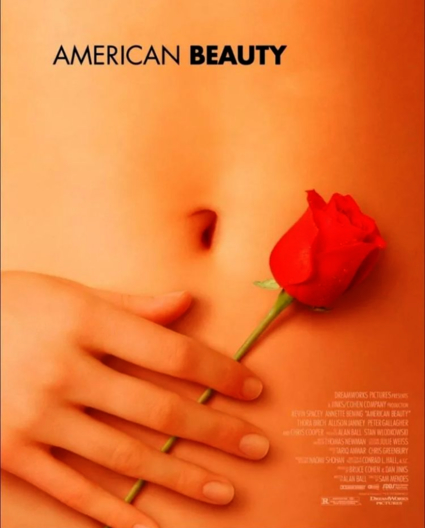

The subjectiveness involved in each of the above criteria is made particularly evident by the fact that contrary to Hansen’s personal suggestion of wild columbine, the national flower of the USA was later nominated to be rose (as it is in England). The following is the proclamation of President Reagan who approved the choice:

Americans have always loved the flowers with which God decorates our land. More often than any other flower, we hold the rose dear as the symbol of life and love and devotion, of beauty and eternity. For the love of man and woman, for the love of mankind and God, for the love of country, Americans who would speak the language of the heart do so with a rose.

We see proofs of this everywhere. The study of fossils reveals that the rose has existed in America for age upon age. We have always cultivated roses in our gardens. Our first President, George Washington, bred roses, and a variety he named after his mother is still grown today.

("Proclamation 5574")

The truth is, the specific rose cultivar American Beauty actually originated in France, not the American continent (Dobransky & Fine). Despite this, a thicket of symbolic meanings and cultural familiarity associated with the plant are referred to in the process of naturalizing the rose as being “native” to the land, of an imagined shared ancestry. By doing so, the rose justifies and normalizes the authority of the state— its hegemonic, Christian, heterosexual value system. In the eyes of Reagan, the sentiments that form rather automatically and “naturally” when one receives a bouquet of roses is unrivaled, especially not with a flower that is unheard of like the columbine. Such renders the rose as potent propaganda. It then appears that political, cultural and materialist (to the extent that roses were already popular in the flower market and its being nominated as the state symbol only encourages this further) interests can readily overcome the true status of the species as a “native” or not. Or more accurately put, the “nativeness” of a species is always already determined by such interests. As Dobransky and Fine claim, “The belief in a plant as “natural” cements its political value, and then the establishment of its political centrality cements its position as “truly natural”.

The process of forming such cement, however, is anything but unified. The US makes for an interesting case as unlike many other countries, it first and foremost acknowledges the tension in recognizing a singular botanical species to represent itself. Prior to the selection of rose as the national flower, each US state was allowed to select a state flower, which would then be collected into a national bouquet, reflecting the nation’s federalist character. Dobransky and Fine describe fascinating stories of how these state flowers were chosen. For example, Oklahoma’s mistletoe, which only grew in the western part of the state, had earned much criticism from those in the east — reflecting regionalisms within regions at its peak. Similarly, after World War II, Alabama’s politicians considered replacing camellia, which was seen as representing a deeply “romanticized notion of southern superiority” of the elite class and not the entirety of the state as it came from Asia, with goldenrod, a wildflower. But many preferred to keep the beauty of high-class gardens over goldenrod, which they saw as "merely a weed which had been transplanted to Alabama by Yankee invaders"— the non-native camellia acquired the status of being a cultured “native”, and the goldenrod that had a relatively longer history in the area, was now “invasive” (Ingram). Discriminatory, elitist and racist overtones in floral politics can also be witnessed in the case of Indiana. When zinnia, a popular garden flower in the region native to Mexico, was selected as its state flower, many expressed their distaste: "The Zinnia elegans, a foreigner, ... is a window box spy, a floral Mata Hari. It's got to go. .... it is a native of Mexico and is in Indiana only by infiltration" (Collier), or as Ralph Stark, an Indiana historian and naturalist put it, "it crossed the Rio Grande from Mexico, probably entering the country as a 'wetback'” (Tolle). Funnily enough, when Laurence Baker, a powerful politician and the largest peony grower in the state, suggested peony as the state flower, Indiana readily accepted it— despite it being native to China and Japan (Dobransky & Fine). Thus the likelihood of a flower being selected also depends hugely on the extent to which it pervades the local botanical industry, in other words, its sponsorship, as was also the case of apple blossom, proposed by apple farmers in New Hampshire who criticized the more popular purple lilac on the basis that it was not native to the region. Upon being rejected as Michigan and Arkansas already chose apple blossom as their state flower (and the connection between apples and hard cider was not a symbolic association that the state wanted to emphasize), the farmers then suggested buttercup which grew easily, but this too was rejected, as being yellow, it was “too political” in reminding people of the suffragette movements (as if floral emblems could be something else other than politics!). In the end, New Hampshire drew a compromise by selecting purple lilac as its state flower and pink lady’s slipper as the state wildflower. We frequently observe that a flower such as the pink lady’s slipper is seen native if it has been there since “"time immemorial"-or at least since before European colonization, which is functionally the same thing”, as also reflected in Utah’s selection of the sego lily, first introduced by the Native Americans to the colonizers who then ate the bulbs. As innocuous as this assumption may seem, such rhetoric often nullifies the culture and history prior to European colonization by pushing it into a mythical and abstract past, a state of purity untouched by mankind (Masnak et al).

The selection of a floral emblem is through and through a question of who is represented and whose interests are served. Recently, the China Flower Association invited citizens to vote for a new national flower of the country, among which plum blossom (the preexistent floral emblem of China) and peony were the most popular (Li). Some netizens suggested using both, the former as the symbol of spiritual character and the latter as the symbol of national strength and prosperity, while others commented that having "one country, multiple flowers" better incorporates the cultural and ethnic diversity of Chinese people. Others even argued that considering that many Chinese cities already have their floral emblems, “identifying one flower as the sole national flower seems unfair”, and that “an opinion poll on whether China actually needs a national flower should be held first”. As of today plum blossom remains China’s national flower, and its botanical characteristics are exploited to the fullest in embodying national ideals:

- The three buds and five petals symbolize the Three Principles of the People and the five branches of the Government in accordance with the Constitution

- The five petals also symbolizes the Five Races Under One Union, Five Cardinal Relationships (Wǔlún), Five Constants (Wǔcháng) and Five Ethics (Wǔjiào) according to Confucian philosophy

- The branches (枝橫), shadow (影斜), flexibility (曳疏), and cold resistance (傲霜) of the plum blossom represent the four noble virtues of "originating and penetrating, advantageous and firm" in the I Ching

(“National Flower”)

While theoretically any item can be nominated a state symbol (in fact, the US has 75 state symbol items including cookies, mushrooms, beverages, soils (Rosenthal), flowers in particular are used to essentialize, sentimentalize and idealize the existence of the states, and their sponsored ubiquity serve as consistent reminders for people to identify with their countries and cultural values (Dobransky & Fine). Even as flowers’ association with the states are not any less arbitrary than that of other items used as state symbols, this arbitrariness creates much space for many parties entering the battleground to dispute over their differing interests. Geographical “nativeness” of the flower is only one of these many interests, and one which can readily be forged.

We conclude this introduction to the fervent debates surrounding floral emblems by mentioning that tulip too — you guessed it — is not a geographical “native” to the Netherlands. To find out how tulip became the flower of this country, follow us to the stories of the Tulp family.

References

Collier, Joe. “Zinnia, ‘Floral 5th Columnist,’ May Lose State Flower Title.”Indianapolis Times, (1941).

Dobransky, Kerry, and Gary Alan Fine. "The Native in the Garden: Floral Politics and Cultural Entrepreneurs."Sociological Forum21, no. 4 (2006): 559-85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4540965.

Hansen, Albert A. "A National Floral Emblem." Science 47, no. 1215 (1918): 365-67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1642214.

Ingram, Bob. “Camellia State Flower.” Montgomery Advertiser, (1959).

Li, Shigong. “How Should China's National Flower Be Selected?.” Beijing Review. 2019. http://www.bjreview.com/Opinion/201907/t20190726_800174352.html

Mastnak, Tomaz, Elyachar, Julia, and Tom Boellstorff. "Botanical Decolonization: Rethinking Native Plants." Environment and Planning D: Society and Space vol 32 (2014): 363-380. doi:10.1068/d13006p

"National Flower.” Office of the President Republic of China (Taiwan). https://english.president.gov.tw/Page/98

"Proclamation 5574". Office of the Federal Register, Designation of the Rose as the National Floral Emblem of the United States of America, by Ronald Reagan. 1986. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/proclamation-5574-designation-rose-national-floral-emblem-united-states-america

Rosenthal, Alan. “Symbolmania.” State Legislatures 31 (2005): 34–36.

Tolle, Alec. “Return State Birthright of Tulip Tree Blossom.” Indianapolis News, (1971).