That technology has had a history of impact not only on the culture that bears it but also on its (generally) attendant art forms is well documented. Various art media, to varying degrees, have evolved in direct response to new technologies. In the late Twentieth Century we live in what is often called the information society; a culture constituted of signals rather than artifacts - or perhaps a new family of artifacts.

That a festival such as Ars Electronica has evolved to deal with the relationship between art and technology would seem to imply that a need exists for such a forum. However, in our world the laws of cause and effect, desire and gratification are not always as straightforward as they once were. The information is scrambled by conflicting signals and ever present noise.

Isolation

Ars Electronica was first held in 1979 and then in 1980, 82 and 1984. It has developed from a small event organised by the artists involved to a quite large, government run show. This has allowed for greater funding, and all the benefits this will bring - however one ponders the political undertones of this support. Why a festival of this kind in what is if not a country town then a small regional centre? Why should such a small center spend many thousands of dollars on art work of a highly experimental nature that is not only isolated from an art context but even more so from its potential audience?

Roll out the barrel

At this years event a certain incipient German nationalism was definitely in the air. Problems arose for the audience with the Germans and Eastern Europeans failing to comprehend the Western European and American contributions and vice versa. This led to total confusion at certain events.

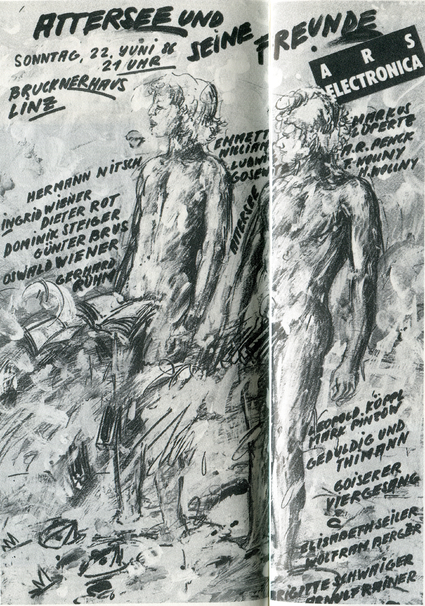

For example, the central event, titled Attersee und sein Freunde was completely incomprehensible to the non-Germanic part of the audience. The Germans certainly loved it, but the rest walked out in frustration. A who's who of German/Austrian art (A.R. PENCK, MARKUS LUPERTZ, HERMAN NITSCH, DIETER ROTH and ARNULF RAINER to name a few) came and went in what appeared to be a roll out the barrel amateur hour with FLUXUS overtones - not to mention new right nationalist undertones.

Strangely, this event, the most publicized and well attended of Ars Electronica, involved no technology (beyond a few microphones and a PA) and did not seek to engage that context. ATTERSEE - whose main reason for being there seemed to be because he is Linz's most famous artist - stated that he wished to show the human behind the machine by focusing on the individual artist. That he succeeded in his subversive intent - calling into question the whole rationale for Ars Electronica- is probable, however if the work he and his friends presented is an alternative then bring on the machines.

Highlights

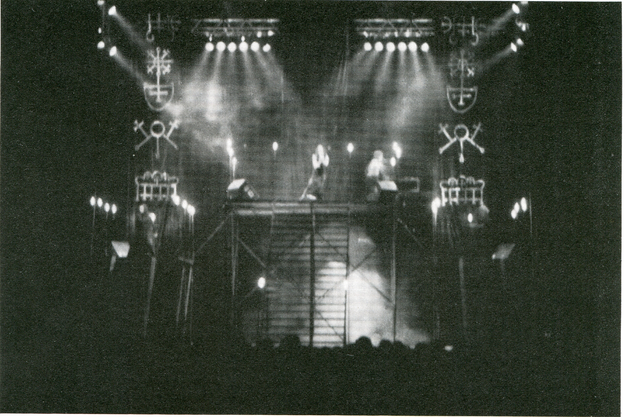

In marked contrast to this example of Austrian self-indulgence was the performance of CABARET VOLTAIRE (UK).

Their slice of life experimental rock presentation - dealing with certain things English (the class structure, urban collapse, identity crisis) and some German (ADOLPH HITLER, control, etc) - was received in virtual silence and received polite applause. I personally found their work highly charged but it was most strange to see an audience remain unmoved through such a spectacle.

An artist with certain things in common with CABARET VOLTAIRE is DIAMANDA GALAS (USA). Her dark, confronting and mysterious work was initially remarkable for its Faustian/phallic symbolism and its ear-shattering volume. Somewhere between WAGNERS Ring and STATUS QUO (via SPINAL TAP), in the end it went on for too long. Perhaps a development of the theme, rather than a constant reiteration, would have helped. However, if this work has flawed, at least it was in the grand manner.

From a completely different tack came the work of RICHARD TEITELBAUM (USA). This work was a real high point, the technology being used in an integrated and transcendent manner. This concert featured works for three pianos - one under direct control of the composer/pianist and the others under that of a computer. Aside from the complex and evocative music this work sought to problematize the whole nature of performance - the status of the performer, his tools and the audience. This set of fundamental relationships, well set in most cases, became fluid and indeterminate suggesting manifold re-alignments of the vectors of communication and meaning that constitute art.

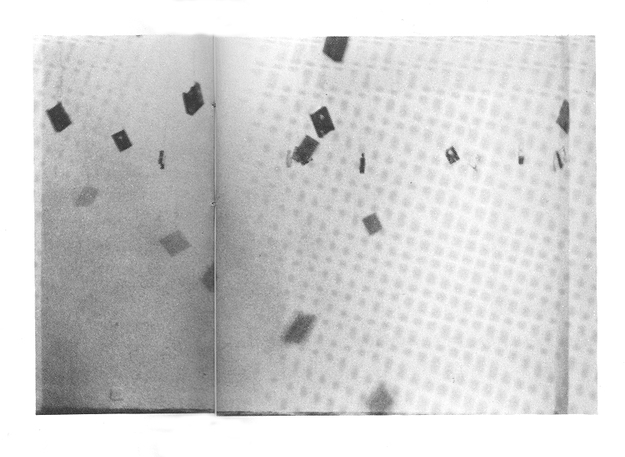

Similarly, the work by FELIX HESS (NL), Chirping and Silence called into question these same basic issues. This piece consisted of a network of small machines capable of talking or singing to one another and the audience. Perhaps more a sound sculpture than a performance - although presented here in concert conditions - this work involved no human performer but rather the machines suggesting many small creatures exhibiting their intelligence and intent thus displacing and deconstructing the roles of reader and writer, performer and audience. Although here the technology was highly visible the result was subtle and completely natural. An elegant moment amongst a great deal of noise.

Terminal Kunst

Amongst all the performances the visual arts made an occasional and attendant appearance. The main exhibition, titled Terminal Kunst, showed a complete lack of curatorial intent or cohesion. The works were without exception very badly displayed and located relative to one another.

The work of Italian video artists GIOVANATTI, MONDANI and MECCANICI was very clever and witty amongst a lot of serious, and seriously lacking, art. Using basic low quality computer generated video they produced a series of small vignettes around the adventures of Futurist theorist MARINETTI. They confronted him with the eventual products of his unrealised labours in a nicely stylised, tongue-in-cheek pop idiom.

Klang Labor, by PETER VOGEL, was a sound sculpture activated by the viewers shadow, creating myriad possibilities in sound and space. Here the sign of both absence and presence, the shadow, was the performance ingredient - the real content/neg-content of the piece.

Ghetto?

This paradoxal metaphor was really at work in Ars Electronica as a whole. The problem here is as follows; artists working in a similar and experimental nature need to get together to develop their work and for mutual support. On the other hand this can lead to a marginalization or ghetto mentality that ultimately isolates the artist and their work from the broader artistic and social context they should be seeking to engage.

Perhaps it is that Linz is the wrong place for an event of this kind, or maybe the fault is with the curators/administrators (who were generally notable in their absence from the proceedings). All up the event failed to engage (beyond a small number of works) and if the stated intention of Ars Electronica - to explore the relationships between the arts, technology and society - is to be achieved a major re-think is required.

If you'd like to quote something: Biggs, Simon. "Ars Electronica." Mediamatic Magazine vol. 1 # 2 (1986).