Precious Patchouli

"Hippie Smell", "old-people-odor", "pure" or just "flowery" - call it what you want. With its unique scent, Patchouli is one of the worlds most popular essential oils. Even nowadays, the plant's characteristics can be found in dozens of cosmetics and products such as air fresheners and laundry detergents.

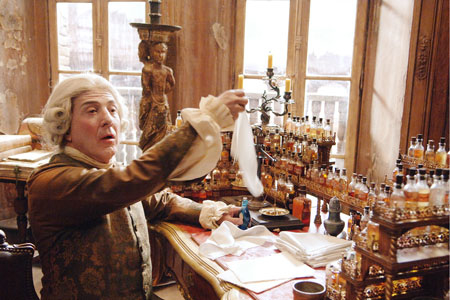

Historically, patchouli was a symbol of great luxury and wealth. This image is speculated to have been born due to its use on the famous "Silk Road" during the 18-19th century, where patchouli was used as an insect repellent during trade transport of fine silks and textiles. With expanded trade of luxuries in the 19th century came the increasingly elaborate concoctions of Victorian perfumes, using many other expensive essential oils layered on top of a patchouli base.

Ressource Problems

However, the scaling up of demand for perfume (no longer considered a luxury reserved for the Upper class in society) meant the industry came to rely on the unreliable nature.

Traditionally, the precious oil is harvested from steam-extraction of the mint-like plant Pogostemon cablin, which is farmed in many countries such as India and China.

Both the quality and the price of Patchouli can fluctuate wildly from year to year, influenced by factors such as natural disasters, labour shortages, diseases or simply a poor growing season.

Indeed, the flavor and fragrance industry experienced a shortage of Patchouli oil in 2010, when soggy weather gave Indonesian growers a poor harvest, stopping many patchouli-dependent manufacturers in their tracks.

Future Smells

It is no wonder, then, that purchasers of fine-smelling and -tasting substances would seek alternatives to nature-grown materials. And luckily, biotechnology came up with a solution: The answer lies in smelly micro-organisms!

Culturing microbes to produce scents is not only cheaper than using naturally sourced ingredients, it also gives perfumers more control over fragrances. As a result, synthetic alternatives to the traditional steam extraction of plant material has dramatically reduced the costs of essential oils.

How does it work?

The logic behind the idea is comparatively simple. In nature, scents come from a class of compounds called esters, which are produced by reacting an alcohol with an organic acid. The ester "Isoamyl Acetate" smells like banana; "Methyl Salicylate" smells like wintergreen. Living organisms also produce esters - yeast for example produces the esters that flavor beer and wine. On top of that, bacteria also produce esters that flavor themselves, for example, cheeses. Just by altering what living cells naturally do, the type of enzymes that the bacteria are producing can be changed - and odors with specific scents can be created. Even though the practice is still in its beginning, surveys and first products show promising results.