Hours were spent in the game centers or coffee shops, plunking down 100 yen coins. The games swallowed up childrens allowances, time, attention, and eventually everything until nothing was left but a generation of Game Otaku. An Otaku did not traditionally exist in Japan. The emergence of Otaku is modern phenomena. In short, it is a general term applied to people who are maniac specialists in certain fields. Hypermaniac enthusiast is a mild term to describe the Otaku. They come in all forms. The Game Otaku will be able to tell you anything and everything about computer games. Similarly, there are Otaku for movies, comics, video art, and so on.

The Famicon, short for Family Computer, completed this game invasion of Japanese society. This gadget designed solely for playing computer games allowed one to play games using the ordinary TV. The product was an immediate hit and a coup de grace that permanently installed the computer game in the living room. The invasion was complete. The incredible blitzkrieg was perpetuated by the irresistible convenience the gadget offered. The formidable combination of the Famicon and TV made trips to the game center obsolete. Famicon software in cartridges gave access to the same game center excitement within the luxury and privacy of the home.

First, children persuaded their parents to buy the gadget. Then older siblings caught the disease. Finally, in some cases, parents even surrendered to the lure of the Famicon. Games ranged from simple action games for children to software for stock trading and semi-pornographic attractions for adults. Older 'kids’ in universities, initially looked down on the Famicon as kiddy stuff. Yet increasing numbers sheepishly began to admit that they had one too. If you had a younger sibling, blame him or her for allowing the Famicon to step through your door. At least this excuse saved your reputation as an intellectual. Only God and the Famicon know the actual numbers of those who play behind closed doors.

Quarrels between family members over TV channels evolved into a new dimension. There were fights over access to the TV or the Famicon. Parental struggles to tear their child away the TV were aggravated by the game. A personal TV, all to oneself, spelled paradise for the Famicon player. What a luxury to have undisturbed privacy with your TV and the Famicon for hours on end. Happiness was complete submersion into the world of games, especially the virtual worlds of role playing games. It did not matter any more if one lost sleep and a sense of real time.

Knowledge of the latest game or fad saved you from social embarrassment. Famicon became a regular topic at coffee break chit chats both at work and at school. And if you haven't heard of Dragon Quest you were certainly out of this world.

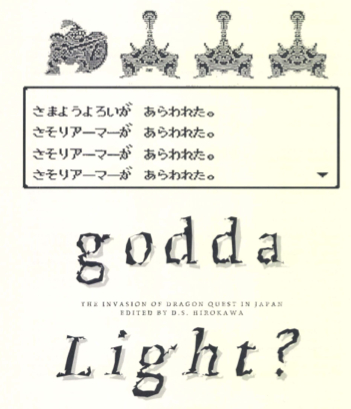

Dragon Quest is a role playing game which allows you to play the role of the hero in a fantasy scenario. In this type of game, the player enters the world with its particular challenges and is allowed to shape his or her own fate. Generally there is a story line which motivates the player to reach a certain goal. For Dragon Quest, the central theme is like that of an ancient epic with warriors slaying monsters and dragons. One character representing yourself and your virtual comrades fight against evil in a virtual world complete with continents and oceans. The purpose of your 'virtual life' is made clear by characters such as your ‘mother’ and other friendly villagers, knights and noble persons whom you encounter. These characters beseech you to save the world from evil. Monsters and riddles make the journey dangerous. As virtual time passes by with a simulation of the day/night cycle, you and your comrades mature with accumulated experience. What started as a band armed with daggers and simple magic spells grows into a formidable team of warriors with magical weapons and wise wizards with powers to kill and heal. In this world you and your friends are the saviours.

As children and adults huddle over the TV, stepping into fantasy land, magazines churn out articles on the latest tips on surviving and conquering in this magical world. Game fans and friends trade tidbits of information. Certain items can be traded for magical weapons. Slay the monsters and you earn gold and experience. A game arena even lets you bet your hard-earned money on two fighting combatants. With luck you have more of a financial edge to buy the badly needed weapon or shield. Fight your way through woods, grasslands, mountains, and oceans. Search for the hermit hiding away in the land of ice in the polar regions. Villages and towns offer safety zones where you can check into inns to rest and heal at a price. Brave bewitched ruins and towers for hints and treasures. And finally when the dragon king is slayed by your sword, do you switch off the game? Certainly not. Reexplore all the continents, castle towns, and villages. The monsters and zombies are gone. The menacing music changes for a cheerful tune. People thank you for saving the world. This is the ultimate ego trip.

Gabin Itoh, technophile editor and critic of LOG IN, a Japanese computer magazine, gives us some insight into the baffling invasion of the Famicon and Dragon Quest. The following comments are extracts from his essay on the Dragon Quest game.

The action role playing game

Dragon Quest 1 was released in May, 1986, and was considered to be the first 'orthodox role playing game' for Famicons. This meant that the game progressed on a command selection basis much like the classical computer role playing games, Wizardry and Ultima.

When Dragon Quest was first introduced, most Famicon games were action games. (Action games like simple target and shoot games engage the player's reflex and do not have stories to tell, ED) At about the same time, the first role playing game boom has been phased out for personal computers and was being replaced by the action role playing game. These were role playing games which incorporated characteristics of the action games. Eventually, action role playing games became so popular that they dominated the entire market. At the time, this [combination of reflex action with a story] was a logical development because the majority of Famicon players were school children who have been addicted to action games.

However the creator of Dragon Quest, Yuji Horii, has created a role playing game without the characteristics of action games. Horii, whose mania for personal computers led to his becoming a game designer, has no doubt been influenced by the classics such as Wizardry and Ultima. One characteristic the game reveals, is Horns attachment to story-telling and/or the urge to create a world with his own hands as a setting for the story. He probably also wanted to create a virtual world for many people to explore and play around in.

As far as story-telling was concerned, there were two available structures for computer games. One was the role playing game and the other was the adventure game. An old example would he Text Adventure produced by Infocom for Apple n. Early adventure games were like mystery novels which led you through paths with multiple branches to pursue. These games evolved from text-only types to stories which were enhanced by graphics. It was more logical to choose the adventure game structure for telling stories. For example, the role playing game Wizardry hardly has any story. The player only wanders around in a labyrinth dungeon, fighting monsters, and strengthening his or her own character.

For what reasons did Horii choose the role playing game over the adventure game, when in fact, he had originally been designing adventure games himself? Several adventure games for personal computers and one for the Famicon have been designed by him. As characteristic of his style, he strives for the user-friendly, easy-to-understand design. This led to the abolition of type-in commands which created problems, for example, when the computer failed to recognize ‘look’ as an equivalent of the registered command ‘see’. He introduced the command selection form where choices popped up in windows. This became a standard style for all adventure games that followed.

However, the adventure game had one structural pitfall despite all the improvements. It was possible for the player to get stuck in a dead-end and have absolutely nothing to do.

After completing Dragon Quest 1, Horii wrote the following in an essay: When you are stuck in an adventure game, there is either nothing to do or you wouldn't know what to do. However in the role playing game, you can keep on maturing your characters. With the exception of extreme cases, the situation of having nothing to do' does not happen. This makes a big difference. Considering games, having something to do'is of course much better than having nothing to do' The popularity of the role playing game proves this fact.

Horii was searching for the best way to tell a story and that happened to be the role playing game. (In effect, he creates a story in which it is impossible to get stuck, ED) Towards the end of the game, the player continues fighting an endless stream of monsters which keeps springing out. Perception, decision, action; at one point these processes detach themselves from the speech control centers of the brain and become machine-like motions or an algorithm that is executed automatically. In answer to the battle program which creates Dragon Quest monsters, one becomes an algorithm that sets out to eliminate these monsters. Language and time disappear and a meaningless process comes to the foreground.

Computer graphic artist, Masaki Fujihata, once defined his works as works of algorithmic aesthetics. What he is trying to do is not to create works but to create an algorithm that creates an artist which in turn creates a work. Algorithms allow the perfect repetition of the creation of a work. The same curves, the same processing of information; in other words, algorithms allow countless works to be reproduced automatically. Take up the weapon called a computer, in the present where maximum speed equals zero speed: I think it is worthwhile to give algorithms some thought. So let’s play games and become algorithms that respond in real time to other simple algorithms.

Secutity instead of originality

Dragon Quest 1 shows the roleplaying game utilized as a system to tell a story. As typical of Horii, the overall structure is simple and easy to understand. The scenario was kept uncomplicated probably with plans to elaborate on it in the next version. He already had the second version in mind while working on the first.

The Dragon Quest story is a simple one of swords, wizardry and heroes. A brave warrior goes out to fight the evil dragon king who’s taken over an otherwise peaceful world. This kind of fantasy story did not previously exist in Japan. Since the release of this game, children play with make-believe shields and swords. Just one game shattered centuries of traditional ninja play and the samurai spirit and replaced it with the spirit of Conan the Great. (This impact on Japanese society in itself is quite staggering, ED)

The story is simple and it lacks originality. Concerning this, Horii the creator of this game says: I don’t care for originality. If I took the pains to add some originality I think it will get in the way. People are bewildered by new things. Games only need to offer fun. In that sense a feeling of security is more important than originality.

In fact, ordinary, matter-of- course, easy-to-understand and user-friendly qualities combined with a technical finesse make up one of the two major characteristics of Horn's games. The other is his above-mentioned love for story-telling.

Dragon Quest z was released in January 1987. The map of the virtual world has been expanded six fold and the number of playing characters has been increased from one to three. The scenario is also more elaborate; the main player meets his comrades who set out on the adventure together and the battle scenes are more tactical with more on the team. The next two versions followed at intervals of one and a half years. Dragon Quest 3 is notable for the most outstanding scenario. And in the final fourth version, the complicated scenario of the third version is toned down to an easier to understand short story structure which results in a beautifully balanced game.

Dragon Quest versions 3 and 4 were heralded with great enthusiasm not only in Famicon magazines but on all imaginable media from newspapers to TV. Everyone wanted to lay their hands on a copy as soon as possible. But the supply was limited. Consequently some children mugged others for a copy. And as usual, each time an incident was reported, the computer-allergic older generation screamed their criticism.

Manga culture

Why do we all love games? Even with Nintendo reaching the global market, Japan is probably the only nation where even adults are hooked. It's puzzling. And as I write this, I become conscious of the fact that I play computer games everyday myself.

In Japanese Pop Culture, which of course includes computer games, another element for which Japanese grown-ups are ridiculed - especially by foreigners - are comic books which are called Manga in Japanese. The amount of Manga distributed in Japan is staggering. At any given time, a look around the train shows several people (grown-ups that is) engrossed in Manga. I consider myself to be an average Manga reader. Let's see... I read about 2 Manga books a day...that's 600 pages a day, adding up to 18,000 pages of Manga in a month. Goodness! Do I really read that much? That's too much. Maybe I miscalculated... no, these are the correct figures. In my working place, most people are interested in Manga and 7 out of 10 read the same amount or more!

There is a strong relationship between games and this Manga culture. First, Dragon Quest is not an offspring of the computer culture but that of the Manga culture. The game designer, Horii aspired to be a Manga writer and was a member of Manga clubs in both high school and university. And he seems to have written a few Manga stories when he was a free-lance writer, ENIX, the producer of this game, creates computer games based on Manga stories. Finally, Dragon Quest's graphic designer Akira Toriyama, is also the in-house Manga writer for the Shounen Jump Manga magazine, a weekly publication which sells about 5 million copies an issue Naturally, Dragon Quest was advertised on the pages of this magazine, a factor which gready contributed to the sales of this game.

Computer games and Manga share a common point in that graphics play the foremost part in the story. I think this is an important part in Japanese Pop Culture. This leads to a problem in the Japanese language. One characteristic of the Japanese language is the existence of powerful conjunctions which act like instant glue. Combined with a grammatical structure that allows for illogical sentences, the power of these conjunctions allows one to freely write incomprehensible sentences.

This is allowed due to the isolation of one island nation, ethnic homogeneity and the lukewarm waters created by one common language; this type of communication is possible only between people with shared experiences and meanings. In other words, the ability to speak, write and read logically has gone down the drain. Manga then becomes a (graphic) tool to help logical thinking or functions as yet another communicative symbol based on a shared experience. At any rate, the Manga mentality and computer game mentality, especially in a 'story' game like Dragon Quest is the same. In fact, most Dragon Quest fans have much in common with Manga readers.

One of the things I like about computers is the escape into virtual reality. Time, space, and distance freeze. There is personal control over all information. In the end, the physical body simply ceases to exist. Of course, on this side of the CRT you have a body sitting and time flowing, but I want to forget that for now and stay submerged in my computer.

Finally, concerning computer games, the speed of technological change has been slow. The slowness prolonged the life of this medium by default. One writes a story using all available capacity. Then technology takes another step providing us with a basis for a slightly larger story. It is like seeing a slow motion process; an observation in the detail of the history of media. Maybe it is suitable for the computer game to become the first medium whose death the school children will witness. It maybe something that allows one respite from the crazy speed of everyday life.

Forget user-friendly security. Computer games have the potential to show us the ultimate game of death with zero speed. I want to see that. Poetry as a medium took a few millennia to mature and die. Novels took a few centuries. Movies took a few decades. And what of TV and videos? The cycle between the birth of a medium and its death has been accelerating. Now some may even be dead as soon as they are born or already dead before their birth. Prolonging the life of the medium is not important. How we deal with dead media is important.

Cabin Itoh and hundreds of others escape into computer games and manga everyday. The comforts of a common language and a shared experience and escape into the virtual worlds of Manga and Famicon land off respite from the crazy pace. After all, one can not sanely face the reality of long boring rides on the crowded commuter trains or the reality of the small stifling apartment. This escape into 'never never land’ may be the safety valve that keeps up the grinding pace of Japanese work and life.

Edited and translated by D. S. Hirikawa