Salt

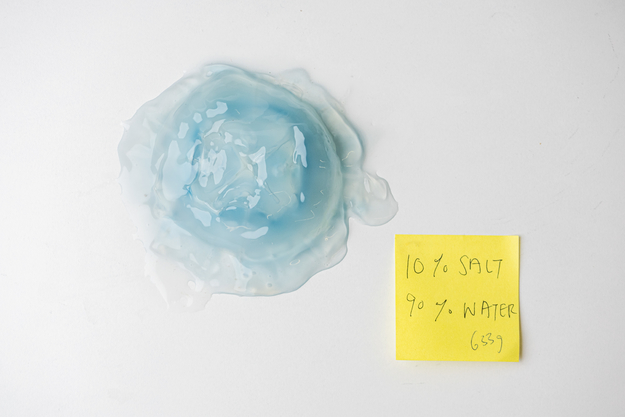

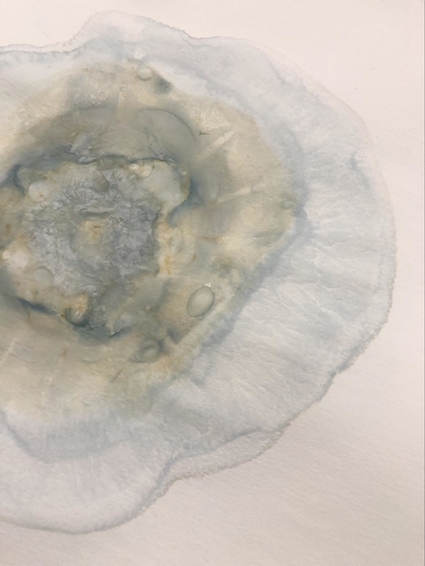

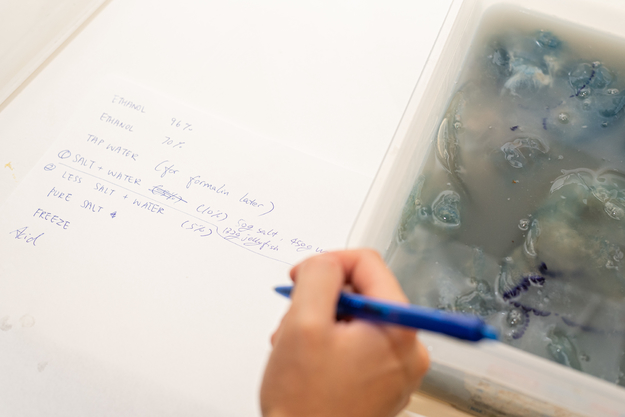

The traditional way of preserving jellyfish for consumption in Asia is a one-month dehydration process with salt (NaCl) and alum (KAl(SO4)2). We did not have access to alum, but tried with various concentrations of salt and water. After 5 days, the higher the concentration of salt in the solution, the better the jellyfish was preserved. The salt did a great job at preserving the barrel jellyfish’s vibrant blue colour. We continued with the jellyfish preserved in salt water by dehydrating it on a filter paper in a dehydration machine in 30 degrees for 3 days. Afterwards, the jellyfish becomes a beautiful print on the paper. Their fascinating structures and colours remain on the paper and even soak through into the paper underneath it.

The jellyfish that was left in pure salt was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the best preserved in its original form of them all. Even after three weeks, though it had shrunk in size as the water had been drawn out of it, it still remained very much in tact but smelled slightly like a dog that had just gone swimming in the sea.

13-11-2019 Jellyfish in salt - Experimenting with Jellyfishes in various substances.

Ethanol

Another method of preserving jellyfish done by a researcher at the University of Southern Denmark for crisps and snacks is with 96% ethanol. After five days of the jellies soaked in ethanol, they had lost all their colour (much like most people would after five days of alcohol). We left them out in the air for another week and by that time they had lost most of their flexibility and became fragile little crisps, somewhat resembling a dried flower, though perhaps a bit more bendable.

Oil

Following these two more established methods, we also tried some other substances. Surprisingly, the peanut oil completely broke down the structure of jellyfish and turned it into a sort of blue-ish liquid. What is behind this mysterious blue is unknown, we cannot find out any information on what gives the barrel jellyfish its vivid hue. The smell was so strong from this experiment after 5 days we had to periodically leave the clean lab for a breath of fresh air, but there is no denying the unexpected beauty in the putrid peanut-jelly liquid.

Acids: vinegar; citric; tartaric

We wanted to see what would happen when you put the jellies in a few acids that we had on hand. The vinegar and the citric acid worked to completely dissolve the main structure of the jelly, leaving nothing but the wisps of jellyfish (presumably collagen) in liquid. The tartaric acid kept the jellyfish in good shape and gelatine-like besides stripping off their colour. There is also a hole in the middle of the jellyfish where the stomach would have been.

Frozen & Sugar

One of our jellyfish specimen was frozen, which left it quite intact, despite many online reports saying freezing jellyfish would destroy the structure. We continued with the frozen jelly by putting it in a jar with sugar, and leaving it for 14 days. The result was a golden, very sweet smelling liquid; quite pleasant compared to the other experiments. There was also a thick layer of sugar settled at the bottom. The jellyfish itself was not dissolved and was pretty well in-tact.

These experiments were interesting to provide foundations in our own knowledge of how a jellyfish looks, feels and reacts to everyday substances around us. However, we still are seeking collaborations in knowledge as to what is possible with these sea creatures. There is much to discover, and much that has already been discovered. Perhaps most intriguing in these exercises is in the beauty of a rotting and attempts at preventing rotting of this sea creature. Stay tuned for more blog posts about the medusae project, and get in touch if you have anything to say!