Though neither are specifically addressed to the ‘problem of the mermaid’ Ulrike Zimmerman’s performance video Touristinnen and the Tom Tom Club’s Suboceania pop clip are both works which simultaneously derive from and critically re-figure aspects of the mermaid and her mythic associations. In this, their projects reflect the peculiarly pronounced resonance of the mermaid as a symbolic figure in Western Culture. For the last thousand years (at least), despite changes in fashions of female beauty, or of social perceptions of the female, ‘femininity’ and sexual difference; the mermaid has been present in a range of visual and literary media - sometimes conflated with her predatory sister, the siren, sometimes cast as an innocent waif (as in Hans Christian Andersen’s famous fairy tale) and occasionally characterised in terms of her promiscuity.(1)

(1) In het zestiende- en zeventicnde-eeuwse gemene Engels betekende mermaid prostituéc dr In Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century English mermaid was a colloquial term for a prostitute.

Whatever the inflection of its uses however, the durability of the mermaid myth is premised on the female nature of its symbolism. This is underlined by the fate of the medieval merman, a figure which has now fallen into such obscurity that the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary extends it a rare quasi-feminist definition as the male of the mermaid. The obscurity of this usage is a significant pointer to the particular potency of the mermaid myth, a potency which derives from historically transcendent aspects of masculine desire and perceptions of sexual difference.

The Female’s Lack

Despite the absence of notable cultural analyses of the mermaid as a fantasy figure, the mermaid is clearly amenable to analysis within both those approaches developed by Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis and those forms of (anglophone) film theory which have drawn upon them. In particular, the cinematic figure of the mermaid is clearly ‘explainable’ in terms of the combination of Freudian and Lacanian approaches employed by Laura Mulvey in her seminal Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema thesis. (2)

(2) published in Serre» vol.16 no.3, fell 1975.

Selectively simplified for the purposes of this piece, the key aspects of this approach emphasise that the crucial difference between the male and female (as perceived within patriarchal culture) is the female’s lack, both physically and symbolically, of the male phallus. As Mulvey argues, drawing on Freud and Lacan, this produces two separate but inter related male impulses - a fascination with the ‘otherness’ of the female which leads to the voyeuristic objectification of the passive female figure, and a parallel perception of the active female as threatening to the patriarchal order and therefore requiring control and/or punishment.

As a number of feminist writers have emphasised,(3) these two aspects are perhaps most clearly manifested in the complex ‘erotic threat’ figure of the, femme fatale as represented in classic film noirs such as Gilda, Out of the Past and Double Indemnity.

(3) See for instance Mulvey (above) and the contributions of the various writers in E. Anne Kaplan (ed) Women in Film Noir London, BFI, 1980.

The aspects of this theory relevant to an understanding of the development of specific versions of the mermaid figure in popular cinema and culture in general, are the concept of lack (referred to above) and the process of reactive fetishisation (particularly with regard to visibility). In the case of the mermaid these are primarily focused on the mermaid’s lower body/tail. Unlike the human female whose uncovered body clearly reveals both the lack of a penis and the presence of labia and a vaginal opening, the mermaid, whose lower body/tail is most often represented uncovered, reveals both a lack of male organs and, like the airbrushed centre-folds of Fifties and Sixties male magazines, an absence of the (supposedly threatening) manifestations of female physicality. Instead, this anatomical absence is compensated for by the presence of a piscine tail apparently unpunctured by female genitalia and usually portrayed (in a classic fetishistic manner) as glittery and golden. This fetishised aspect is further compounded by another convention of the physical portrayal of mermaids (a factor resultant from continuing social taboos around female nudity), the depiction of their (unclothed) breasts covered by luxuriant tresses of cascading (blonde) hair - the further obscuring of a primary sexual aspect by a secondary fetishisation.

Centrefold Sensuality

The most developed representations of the mermaid in the audio-visual media have, to date, been those in die three feature films Miranda (directed by Ken Annakin, UK, 1947), Mr Peabody and the Mermaid (directed by Irving Pichel, USA, 1948)) and Splash ! (directed by Ron Howard, USA, 1984). The mermaid figures of these films adhere closely to the stereotype sketched above and are all emphasised in terms of their seductive beauty - all three being played by young curvaceously slender actresses with (highly styled) long (blond) curly hair. Similarly, in the classic manner, their lower bodies are modelled on the rear third of a fish, but with the tail fin transposed from a vertical to a horizontal alignment.

While the two Forties features Miranda and Mr Peabody and the Mermaid are particularly interesting by virtue of originating from a period when the mermaid sign was in active use in a variety' of popular cultural media;(4) it is Splash', and Daryl Hannah’s physical portrayal of its mermaid Madison which both represent (and significantly reinforce) the contemporary version and inflection of the mermaid my'th which Ulrike Zimmerman’s feminist performance video Touristinnen radically re-interprets and the Tom Tom dub’s Suboceania video offers an alternative symbolic configuration of.

(4) A factor emphasised by the fact of both Miranda and Mr

Peabody and the Mermaid being adaptations from other media: Miranda was adapted by Peter Blackmore from his successful West End stage play of the same name. Mr Peabody and the Mermaid was based on Guy and Constance Jones’ novel Peabody’s.

In contrast to the active negotiation of the mermaid sign in the Forties, when the mermaid figure was mobilised and interpreted in a variety of ways, the contemporary version of the mermaid, as represented in Splash', is a far more prescribed and unambiguous icon. Both prior to Splash', and after the circulation of the film’s specific mermaid image, a standard visual convention became established for the Eighties (anglophone) mermaid - a blond, voluptuous, golden tailed figure closely aligned, both visually and associatively, with the figure of the softcore centre-fold model.

This aspect is strongly emphasised in Splash'.’s representation of its mermaid figure. Madison’s active (and agile) sexuality', offered immediately and unconditionally to the films’ male lead Allen Bauer (played by Tom Hanks), reflects the archetypal male fantasy articulated in the operation and implicit promise of the soft-core pornographic magazine centrefold and the (female) star of the soft-core pornographic film.(5) Indeed, so pronounced is this reading that it is foregrounded within the film text itself where Allen’s brother Freddie is depicted as being obsessed with the soft-core magazine Penthouse. (In fact the script name-checks the magazine so much that one suspects a paid ‘product placement’).

(5) For a description of the operation of the centrefold sec Roger Cranshaw ‘The Object of the Centrefold’ Block no.9, 1983.

This emphasis on Madison’s sexual availability is further reinforced by one of the major differences between Madison and her two filmic predecessors, Miranda (in Miranda) and Lenor (in Mr Peabody and The Mermaid), namely the transformative nature of her physique. Unlike Miranda and Lenor, Madison’s body can transform to full human form by the simple act of getting wet, and thereby acquire legs, full human resemblance and the genitalia required for human sexual congress.

Fluidity and the Phallic Female

The mermaid in Ulrike Zimmerman’s video Touristinnen (played by the performance artist Zora) resembles Madison in that her physique is similarly transformative but differs significantly in both the context of her use and the nature of her visual representation. The mermaid figure in Touristinnen offers a radically alternative interpretation of the myth. Unlike the culturally ‘prefered’ use of the mermaid figure in Splash!, Touristinnen offers a version specifically constructed outside the context and discourses of heterosexual desire and, as significantly, outside the broader symbolic contexts of patriarchy.

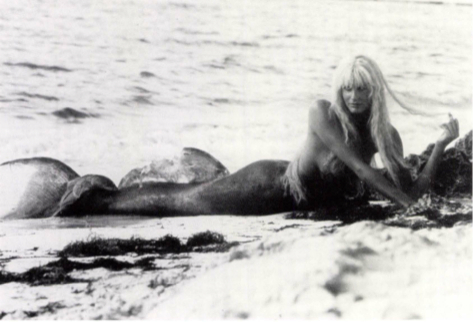

Touristinnen is a twenty five minute video comprising a number of linked ‘performance scenarios’ enacted by various women in a largely deserted area of docks. One aspect of the overall narrative includes the arrival of a mermaid in the harbour, her coming ashore on the invitation of one of the women, the (unseen) transformation of her tail to legs and the establishment of a relationship between the woman and the mermaid through a number of shared activities. Within this scenario Zimmerman constructs a distinctly alternative version of the classic mermaid figure. Unlike the mermaid figures discussed so far, Touristinnen's mermaid deviates from conventional representations by both having short cropped hair (cut in a wavy zigzag pattern) and bare breasts. These are not simply details however, the absence of the traditional tresses and the (‘blatant’) exposure of her breasts creates an assertive image firmly at odds with the coyness and passivity of the previously described filmic mermaids.

In place of the passively acquiescent figure of patriarchal myth so neatly characterised by the German release title of Ron Howard’s Splash! - Die Jungfrau am Haken (‘The Virgin on the Hook’); Zimmerman and Zora’s re-interpretation of the mermaid constructs her as an autonomous female figure rendered inexorably exterior to male (patriarchal) society by virtue of her absent genitalia and her consequent inability to bear children. Rendered exterior to the symbolic order of sexual difference Zora’s mermaid figure becomes, in the terms of patriarchal discourse, the (symbolically) phallic female.

This phallic aspect carries over into her specific visual representation, which echoes the representation of the filmic femme fatale. As Zimmerman confirms: ...the image of the woman with her over-sized tail is also intended to be phallic... in the sense of the phallic image of the screen goddess in popular films. The narrow skirt, high heels and gloves continue this image on land: the sensuous woman - erect in appearance (6)

(6) This and all subsequent quotations are taken from an interview with Ulrike Zimmerman - translated by Julia Knight.

Zora’s mermaid is therefore akin to the powerful film noir femme fatale but ‘superior’ by virtue of her complete exteriority to patriarchal society and the restriction of male desire. The rich and radically alternative representation of the mermaid in Touristinnen reflects both Zimmerman’s own sexual-political perspective and also the plural nature of the mermaid figure in German language-culture. Along with the literal equivalent of the mermaid (Meerjungfrau or Seejungfrau), German also offers an alternative use of the Nixe (water nymph), a figure in itself which can also be specified as a mermaid (Nixe mit Fischschwanz) or a ‘bathing belle’ (Badenixe). In addition German culture also offers adjacent figures which not only include the classical Sirene and die specific figure of the Lorelei, but also other monstrous demi-human females such as the Melusine. In this sense, the mermaid of Touristinnen is more precisely eine Nixe - a term independent of the connotations of virginity attached to the two literal translations of the term mermaid; and as such her nature is not defined in relation to her ‘maidenhood’ and its significance in heterosexual transaction. But in addition she also shares, at least associatively, the power of the Lorelei - the soulless killer of men...

Despite the challenging power of the Lorelei and Melusine myths, it is not Touristinnen’s threat to masculine power which is its key emphasis, but rather its exteriority. Touristinnen does not create a world/context (explicitly) against men and masculine discourse, rather than one simply without it. In place of the precise regimes of male language, power and logic, Zimmerman emphasises her conception of the figure of the mermaid and her realm as imagined by intuitively pursuing a mixture of myth and a desired image of bodily qualities which was related to the water ...a body which, through its closeness to the water becomes fluid, sensuous and mysterious.

Touristinnen, therefore, like Splash!, Miranda and to a lesser extent Mr Peabody, evokes those theorisations of the distinct fluidity of female discourse argued by Luce Irigaray in reaction to the work of Jacques Lacan. (7) However, while the mermaids of the three films had access to powerfully affective language forms outside thelogocentric nature of terrestrial speech, Zora’s Nixe is speech less. In this sense alone, the films, and Splash! in particular, arguably offer a more radically disruptive aspect than Touristinnen. While the mermaids in Miranda and Mr Peabody and the Mermaid possess a seductive melodic form akin to the more threatening siren’s song, Madison’s language is a true ‘other’ to patriarchal speech discourse - when Madison speaks her name in her own tongue, its sound is so abrasive it shatters TV screens and silences the (masculine) babble of the media. The potentially subversive force of Madison is revealed, elle a un language de poissarde...

(7) Succinctly summarised by Jane Gallup in Feminism and Psychoanalysis: The Daughter’s Seduction London, Macmillan, 1982 - sec particularly pp38-42.

The (sub)oceanic Sublime

Somewhat surprisingly for a (commercially functional) video clip, the Tom Tom Club’s Suboceania pop video offers an even more radical refiguration of myths of the female, and a female fluidity exterior to terrestrial society and patriarchal discourse, than that offered by Touristinnen. In place of the mermaid figure, one which however re-inflected is essentially derived from male perceptions of desire and sexual difference, the video offers a radically different mythic figure symbolising aspects of female power and fluidity.

The figure chosen to express and embody these symbolic aspects of the female and essential femininity in Suboceania is, if possible, both more alien to the human form than even the fish and more symbolically sublimely than the mermaid’s incoherent juxtaposition of fish and female physique. Suboceania’s female presence, acted by the Tom Tom Club’s lead singer and bassist Tina Weymouth, is modelled on the delicate, gossamer tendrilled and translucent acaleph (the jellyfish) - a creature significantly only tenable in its aquatic environment. Through a series of careful dissolves Weymouth, resplendent in layers of diaphanous gauze descending from an elaborately large mantissa, blends in and out with images of the acaleph figure floating in water - identifiably female, but also, identifiably ‘other’. The song’s loosely associative lyrics are sung by Weymouth in a mellifluous siren-like voice and offer the constant invocation Lets stay down under/way, way down deep\ a call which lures a male figure (played by Tom Tom Club drummer - and Weymouth’s real life husband - Chris Frantz) down into the water in a rippling vortex. The seductive world she sings of is one, akin to Irigaray’s orders of fluidity, where time and progeny are conceived of in fluid terms, one where this is your life after and (simultaneously) this is your creation; where the fluid figures are timeless, where - we are the future/from out of your past...

From its loosely associative lyrics, sinuous musical flow and startling visual imagery, Suboceania creates a fluid amniotic realm transcendent and radically ‘other’ to the symbolic order of patriarchal masculinity'. This is further emphasised by the theme of procreation which offers a reverse of the scenario of Miranda. Whereas in Ken Annakin’s 1947 film, its eponymous mermaid comes ashore to find male partner(s) to father a mer-child, it is the entry of Frantz into the suboceanic domain of the video clip which prefigures the (literal) water-birth of a child, calmly delivered into the fluid world by the simple unforced opening of a shell and the introduction of a child gazing in unfocused delight at the waters around him.

If Suboceania can eventually be read most convincingly as an expression of aspects of Wey'mouth and Frantz’s relationship and their attitudes to partnership and ideal procreation, this does not undermine the forceful originality of the symbolism it creates. Just as Touristinnen successfully re-appropriates the male derived

mythic figure of the mermaid for its lesbian feminist discourse, Suboceania offers an alternative mythic figure and (fluid) context for both heterosexual desire and procreation which is also radically ‘other’ to cultural convention.