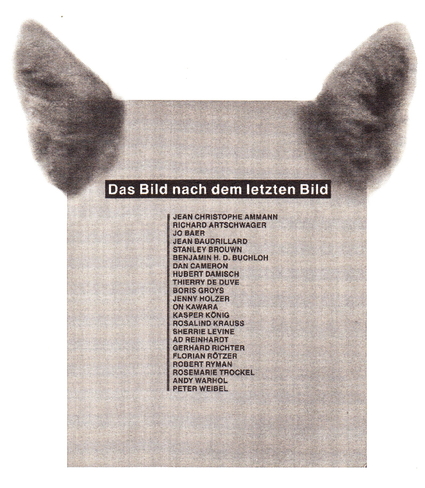

There is something (unintentionally) anachronistic about Galerie Metropol staging an exhibition on 'the last picture' in this kind of art-trade enclave. The works of Richard Artschwager, Jo Baer, Stanley Brown, Jenny Holzer, On Kawara, Sherrie Levine, Ad Reinhardt, Gerhard Richter, Robert Ryman, Rosemarie Trockel and Andy Warhol which were shown in this context once again made it overly clear how radically the definition of the concept 'picture' has changed in this century.

There are different kinds of 'last pictures', but one symbol towers above them all: the monochrome canvas that represents, simulates, substitutes nothing.

The icon – in this field there are always allusions to a sacred transfiguration of materiality – of these termini is the black canvas. Over the course of this century, a series of Black Paintings (Malevich, Reinhardt, Rothko, Artschwager, Law, Charlton, etc.), each made according to a different aesthetic premise, has seen the light of day. This list, which illustrates the cyclical aspect of the 'last picture' discussion, was represented in the exhibit by one of Reinhardt's 'ultimate paintings'. In his contribution to the exhibition catalog, The Last Will Be the First, Dan Cameron more closely examines this circularity, in which he identifies a parallel with events in the economic sphere. Cameron is of the opinion that it is useless to pose the question of 'last pictures'. To him the avant-garde is an archetypal myth endlessly repeated over the past hundred years. At the moment we have nothing to replace this myth of eternal reappearance. Thus, although the classical avant-garde, which was entrenched in modernist linearity, has presently been played out, the idea of an avant-garde remains definitive. This gives rise to a post-avant-garde, which loses its critical function and endlessly repeats stylistic effects. In this context Cameron writes of a 'pseudo-vanguard'.

Cameron is the only one who takes a critical swipe at the concept of the exhibition; the other authors do not commit themselves. Jean-Christophe Ammann deconstructs the exhibition plan formally, but otherwise rather meaninglessly, from his perspective as a museum director. Kasper König superficially paraphrases the exhibited work. Hubert Damisch offers a sterile epistemology of the picture concept. In a lovely allegorical story of two painter friends who evolve from figuration to the virgin canvas, Thierry de Duve metaphorically reconstructs the history of the last picture', without neglecting to immediately suggest its relativity and irony. Four monographs are included in the catalog: two on Warhol, by Jean Baudrillard and Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, one by Rosalind Krauss on Sherrie Levine, and one by Florian Rötzer which examines the reception of Ad Reinhardt.

The publication contains two more interesting essays. In The Suffering Picture, Boris Groys refers to the simulacrum character and the loss of critical function which characterize contemporary art production. Finally, Peter Weibel's The Picture after the Last Picture is an art-historic genealogy of the 'last picture' whose point of departure is Mallarmé's poem Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard. For Weibel, a continuity is possible in the 'last picture'. He bases this idea on Bachtin's idea of infinite contextuality. In literary theory Bachtin gets credit for having done away with the classic autonomy of the author and the text. The text is hereby situated in an infinite field of possible interpretations. He treats visual art according to this notion of intertextuality. From this point of view, termini are perpetual, functioning in our consciousness as calibration points and spearheads. To Weibel there is no such thing as a 'last picture'. The 'last picture' is always the last picture of a historic way of looking at pictures.

It is regrettable that the exhibition which Weibel helped to put on in Metropol insufficiently examined the picture's current historical situation and its consequences for our experience of reality. Most of the works in the wide range of recent 'last picture' productions are done within the frame of reference of post-avant-garde processes (post-minimalism, post-conceptualism, post-fetishism, post-Beuys to name one name, etc.). These works are done not out of necessity, not for the sake of their critical function (unless self-referential), not even as paradoxical statements, but so they can circulate in museums and the art trade. This kind of work dominates Das Bild nach dem letzten Bild. The question is, why does criticism keep hermeneutically legitimizing this closed circuit? Driven by the automatic pilot of the market mechanism, intra muros events in fact set the standards of the art scene.

This is also, naturally, an ideal breeding-ground for museum strategies. Illustrative are the works by Jo Baer, Stanley Brown and Richard Artschwager presented in the exhibition. They still take the path of deconstructing the classical picture concept by investigating the picture's components (the frame, the canvas...). A typical example is Jo Baer, who like Sam Francis and others works on the edges of the canvas and so deconstructs the hierarchy of the traditional canvas, which assumes presence in the centre. It is this strictly self-referential formalism, presented in the form of a mingled playful anecdotism and an ecology of emptiness, which is something to think about in a time of image saturation and sign-entropy. Such a scientific context – call it a rearguard action of the autonomy of the art object – cannot be of interest to us. Not the mutations the picture extra muros is subject to, but thinking, is the true challenge. Amid all this flirting with the autonomy of the art object Warhol's work is refreshing. Warhol has definitively passed the stage of the reification of the art object. He considered the art object in a radically different way.

It is no accident, then, that the two most interesting monographic articles in the catalog deal with Warhol. In his article Mechanical Snobbery Baudrillard discusses Warhol in connection with hypostasis, namely the picture as a substance which stands on its own and is a carrier of sociocultural and ideological processes. Warhol is not part of the history of art, he is simply part of the state of the world – our world. He does not represent it, he is a fragment of it, a fragment in its pure state. According to Baudrillard Warhol realises a fetishistic transmutation of image and sign. After the object has liberated us from representation, Warhol liberates us from art and its critical utopia. Baudrillard fits Warhol neatly into his philosophy of the disappearing world, in which universality, alienation-emancipation, and the object-subject dichotomy are lost. He calls Warhol?s work an anthropological challenge for art and aesthetics. Benjamin H.D. Buchloh endorses this in The Andy Warhol Line by investigating Warhol's ambivalent relationship to the cultural industry.

According to Buchloh, Warhol takes to the hybrid fusion of elitist art and mass culture like a fish to water: Artistic objects participate enthusiastically in a state of general semiotic anomie, a reign that Warhol called 'business art business'. Warhol's work proclaims the time frame, social space, a referent, making his work exceedingly suitable for cultural-critical examination.

In their introduction, the curators König and Weibel ask, Can a work of art survive today in a form other than that of a theoretical object? Of course not; this is kicking down an open door. What is problematic about the catalog is that the arguments are almost exclusively waged within the territory of the art-immanent. This of course has much to do with the selection for the exhibit. Apparently there was no ambition among the compilers to extend the last picture debate, a mandatory art-critical theme issue every so often, in an anthropological sense. Warhol was the only exception. This is regrettable, because instead of preaching to the converted, in an eschatological sense enough can certainly be said about the world and the art object.

translation laura martz