A peculiar child

Ranft presents various historical texts which describe Hildegard’s childhood, and draws connections to characteristics commonly found in autistic children. Among these characteristics are 'impairments in verbal and nonverbal communication' as well as 'delays in social communication before the age of three years', and 'restricted or repetitive interests and behaviour'.

Hildegard, being the 10th child, was selected by her parents as a 'tithe offering' - 'tithe' being the tenth part of a person’s income or possessions which was commonly donated to the church.

Ranft hypothesises that 'Hildegard’s parents may not be the ones who imposed her social isolation'. Instead, it may have been her own character which separated her from others. Ranft cites Guibert of Gembloux [1124/25-1213], who wrote that the young Hildegard 'was in truth completely set apart, since from her infancy she made herself a stranger to all the cares and all the children of the world'. He also noted that she 'shrank from the embarrassment and was slow to obey', a trait that endured well into her mid-life.

Hildegard herself reported a 'weakness' she had felt for almost her entire life: 'a recurring ailment I have suffered from my mother’s milk until now, which wore out my flesh and sapped my strength'.

Ranft summarises: 'Hildegardian sources describe a child […] beset with an undefined 'weakness', social isolation, deficits in expressive oral communication, difficulty in expressing needs, extreme distress at failed attempts at relationship and withdrawal in the face of failure.'

Adulthood: Unfolding her potential

According to Ranft's sources, Hildegard's childhood struggles did not disappear when she reached adulthood. She was still known for 'her silence and fewness of words' during her early adulthood and reported on a 'fear of people at the time' in her own writings, which she dictated to a scribe, since she herself had difficulty with learning to write. 'Together they devised a strategy to break through Hildegard’s communication barrier by stressing written over oral communication.', Ranft writes. She also seemed to have episodes of obsessive behaviour, during which she 'received the heavenly command to change her place of dwelling…Sometimes she would suddenly rise from her bed and walk around all the corners and rooms of the anchor hold, all the while unable to speak'.

However, these difficulties did not hinder Hildegard from pursuing her interests, and gaining power within and outside her monastic community. Ranft writes that after the passing of her teacher Jutta von Sponheim, 'with unanimous consent of her sisters - for they were secure concerning her discernment and self-control - [Hildegard] was chosen to exercise the supervision of discipline over them'.

She demonstrated innate musical abilities, which Ranft states are 'consistent with savant skills that approximately 10% of the autistic population possesses (as compared to 1% of the general population)'. She also composed the two strictly structured treatises Physica and Causa et Curae.

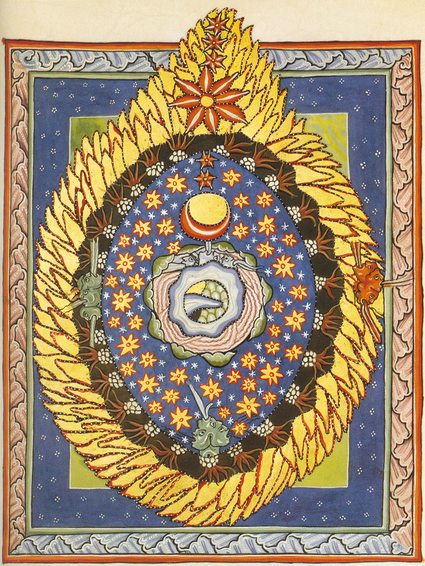

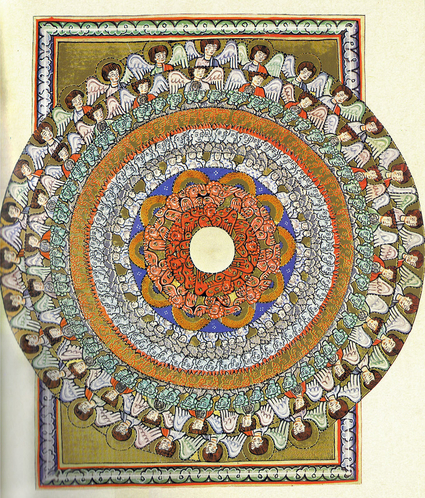

Illustration from 'liber divinorum operum' - Image by Nathaniel M. Campbell , found on his blog .

Ranft writes about autistic individuals: 'their single-mindedness and willingness to abandon outside interests are frequently the formula for success, particularly in science, art, and music'. This description seems to fit perfectly the picture that Ranft paints of Hildegard.

Another notable point that Ranft brings up is Hildegard’s documented “close association with the mentally/socially disabled“. There are several witness documentations about Hildegard allowing mentally ill women into her monastery, with some of them recovering during their time spent there. Ranft describes this as an 'advanced understanding of such disabilities as distinct from demonic possession' on Hildegard’s part. It is easy to speculate that this advanced understanding could have come from her own experience with neurodiversity.

A vivid visual thinker

One of the things Hildegard was most famous for in her time and beyond were her visions.

She described one of her visions like this:

'In this vision I understood without any human instruction the writings of the prophets, of the Gospels, and of other saints and of certain philosophers, and I expounded a number of their texts, although I had scarcely any knowledge of literature, since the woman who taught me was not a scholar. Then I also composed and sang chant with melody, to the praise of God and his saints, without being taught by anyone, since I had never studied neumes [in plain chant, a note or group of notes to be sung to a single syllable] or any chant at all'.

Hildegard was adamant that what she learned in her visions was visual, not mystical, knowledge: 'I never suffer the defect of ecstasy in these visions. And fully awake, I continue to see them day and night'. Ranft writes: 'Hildegard’s dependency on visual learning is near total: 'I have no knowledge of anything I do not see there, because I am unlearned''. And further: 'Hildegard believed that her visio was 'linked in a mysterious way with her recurrent bodily afflictions'.

Ranft hypothesises that Hildegard's visio may in fact correspond to 'the unusual sensory experiences of many [autistic] individuals'.

Hildegard’s texts also mention her excellent memory: 'Whatever I see or learn in his vision I retain for a long period of time, and store it away in my memory. And my seeing, hearing, and knowing are simultaneous, so that I learn and know at the same instant'. Ranft adds that 'a highly retentive memory is another frequently documented characteristic of [autistic] individuals'.

Ranft also poses that Hildegard was likely hyperlexic: 'Typically the hyperlexic person learns visually, has significant difficulty with verbal language and has a precocious reading ability. This describes Hildegard.' Hyperlexia is also trait commonly found in autistic children.

To summarise, Ranft writes that Hildegard posessed a 'highly imaginative, visually oriented intellect' that pictured structures and events 'in an entirely unique and creative manner'. It may be that she is so successful at this because, like many [autistic] individuals, an objective approach and visionary involvement in cognitive processes came naturally to her.'

The monastic life: an ideal environment?

Ranft explains why she believes that in case Hildegard really was autistic, her parents made exactly the right choice in sending her to the monastery under the care of Jutta von Sponheim. She writes that Jutta was an “excellent teacher concerned with matters beyond the spiritual; she possessed 'wisdom both in spiritual matters and in dealing with various other needs', including adapting to each individual student’s personality.

Ranft then lists characteristics of the monastic life which may be beneficial for autistic individuals:

It is 'highly structured, individualised with low teacher/student ratios, demands hierarchical relationships and intense engagement, offers systematic teaching and encourages family/community involvement'. Further, 'scheduled periods of silence would eliminate undue pressure on learning effective communication skills; the chanting would present an ideal situation for gestalt language learning techniques.'

And finally the monastic schedule also included a 'daily Chapter where the community gathered to tend to the day’s business; Chapter was also where a woman could discuss her failures, problems and limitations, and receive feedback from the Community', not unlike a daily therapy session.

Conclusions

Patricia Ranft summarises her claims as follows: 'Hildegard had some very specific abnormalities as a child. The sources report that her parents searched long and hard for a school and a teacher who would fit her needs. They inform us that, after years of living a structured life under close supervision, Hildegard was a high-functioning adult, capable of leadership within a group of similar individuals.'

She also concludes that 'medieval monasticism, however unwittingly, was well suited for fulfilling the secondary function of integrating a spectrum of behavioural phenotypes into its life.'

On the nature of ruminations and notes on this paper

The title of the paper, 'Ruminations on Hildegard of Bingen and autism', is of course carefully selected. 'Ruminations' are not hypotheses or claims to truth - they are simply wandering thoughts. While the author does present her arguments in a structured way, she also recognises that it is not possible to make any definitive claim about the neurotype of a person who lived a thousand years ago, complicated as it is to make such a claim about someone living today.

What this paper does, then, is not to try and retro-diagnose Hildegard von Bingen as autistic. Instead, it presents a compilation of evidence which illuminates the possibility.

Another important point is that the paper is from 2014, and uses some outdated terminology around autism. For example, the author refers to the DSM-4 instead of the most recent DSM-5, and compares the monastic environment to 'treatment programmes' for autistic children, whereas we know today that autism is not a condition that needs to be treated and improved to match neurotypical behaviour.

Patricia Ranft herself has stated that the paper is by now 'happily out of date'.

Still, it contains valuable insights and is very relevant to our research into both autistic role models throughout history and the example of monasteries as places of (assisted) co-living and co-working.

Reference:

Ranft P. Ruminations on Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) and autism. J Med Biogr. 2014 May;22(2):107-15. doi: 10.1177/0967772013479283. Epub 2013 Jul 29. PMID: 24585581.