28 jul 2023

The Mind Garden: Thoughts and Inspirations

Explore connections between gardening and neurodivergence.

A/artist has been developing the concept of Mind Garden for the past few months. After the roundtable discussion: Plants are it!, where guests shared their practice and thoughts about plants and gardening, our research continues exploring connections between gardening and neurodivergence. What benefits do gardening provide to alternative minds? How can neurodivergent individuals use the garden to express their inner worlds? This article gives a closer look at how gardening connects plants and the mind, and its possibility for neurodivergent individuals to enrich and express their minds.

Plants, Garden, and the Mind

The garden exemplifies human-nature interaction through the mindful process of cultivation. From seed to fruit, the slow, quiet and attentive process of cultivating is sensory-friendly to neurodivergent people.

The growing process of plants also demands the gardener to follow the rhythm of nature, helping to develop a personal routine that has close connection to the entire garden space: its climate, soil and all kinds of life forms. This is a mindful activity that helps attune body sensations with surroundings. It invites the gardener to perceive the environment from other-than-human perspectives: do I feel thirsty? Is the soil energising enough? What would be a comfortable temperature?

As Sue Stuart-Smith contemplates on her experiences of gardening1, “Sometimes when I am fully absorbed in a garden task, a feeling arises within me that I am part of this and it is part of me; nature is running in me and through me.” The mind is opened and growing with the nature through caring of the garden.

In horticultural therapy, contacting with nature and caring of gardens are developed as healing approaches to promote sensory integration and build social skills in young individuals with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD)2. Plants offer various sensory stimulations such as colours, textures and smells. And the garden brings spatiality to the sensory richness. It highlights the embodied interactions between individuals and their surroundings.

For neurodivergent individuals, these interactions may be influenced by factors such as stimming behaviours, communication styles, patterns, and sensitivity to different stimuli. The enclosed, protected space of the garden also provides feelings of safety and pleasure. Sue Stuart-Smith describes the garden “offering a feeling of safe enclosure without entrapment”, where emotional holdings can be open at a protective space3.

Gardening involves problem-solving, planning, and decision-making, which can provide cognitive stimulation and improve focus and attention. Meanwhile, witnessing the growth and development of plants can be a tangible and fulfilling experience. Neurodivergent individuals can find gardening to be a fulfilling and therapeutic activity.

Express the inner world

A garden created by a neurodivergent individual can be a unique and expressive reflection of their inner world, experiences, and interests. The plant selection and garden layouts may showcase a diverse range of sensory experiences. It emphasises the significance of lived experiences over fixed categories and representations for diverse neurological profiles.

Many societal understandings of neurodivergent individuals tend to focus solely on deficits or challenges associated with their conditions, overlooking their unique strengths, abilities, and perspectives. Understanding sensory engagements and nature co-creations of neurodivergents in the garden can provide valuable insights into their perspectives and needs, contributing to the richness of human experiences and expanding our understanding of the world.

In art and literature, the garden has been used as a metaphor for centuries, representing a rich and multifaceted symbol that encompasses various themes and ideas. Different elements within a garden, such as plants, paths, and structures, can represent various thoughts, emotions, and memories. Artists and writers use this metaphor to depict their inner worlds and explore themes of self-reflection, introspection, and psychological states.

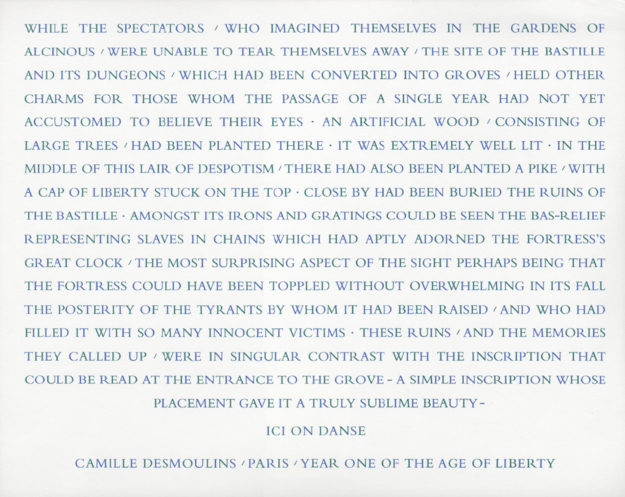

One notable example is Ian Hamilton Finlay, a Scottish artist and poet. Finlay's artistic practice often involved the creation of poetic gardens, where he combined visual elements, sculptures, and text within a natural setting. These gardens served as a reflection of Finlay's inner world, with its poetic and symbolic language inviting visitors to engage with his ideas and narratives. Through his art in the garden, Finlay aimed to create a contemplative space that encouraged reflection, connection with nature, and an exploration of the relationships between language, art, and the environment.

Paul Klee had a deep affinity for the theme of the garden in his artwork. Klee's gardens often served as metaphors for various ideas and emotions related to growth, transformation and playfulness4. Klee unfolds realms of imagination, inviting viewers into spiritual states through his colourful, abstract impressions on the garden and its metaphors.

Plants for the Mind

With the help of herbalist Lynn Shore, we created a list of plants that shows linkage between the garden and neurodivergent minds. Most of the plants can be found at garden containers (Hortus Dijkspark) around Mediamatic:

Lamb’s Ear (Stachys byzantina)

Stimming

The foliage of Lamb’s Ear has a unique look and texture. Thick, soft, oblong-elliptic leaves and densely white-woolly stems invite you to touch. Also, the plants is easy to grow and can sometimes be found growing in the wild.

Feather Grass (Stipa tenuissima)

Stimming

The dense, fountain-shaped clumps of feather grass stems have a fuzzy appearance; they soften the landscape. When running your fingers through the grass blades, you may notice a delicate and wispy sensation, similar to touching feathers. The texture varies depending on the species or cultivar of Feather Grass.

Bamboo (Bambusa spp.)

Sound stimulation

Bamboo plants can create sound when the wind passes through their culms and rustles the leaves. The plant is commonly used to make traditional flutes and percussion instruments in many cultures.

Coleus (Coleus)

Visual stimulation

Offers all-season vibrant colours. The foliage varies widely in shape, style, and colour.

Peppermint (Mentha × piperita)

Olfactory stimulation

Peppermint has a refreshing and cooling effect, which can help to revitalize the senses and provide a sense of wakefulness. In aromatherapy, inhaling peppermint essential oil is commonly used to help combat fatigue, improve concentration, and alleviate headaches.

Lavendel (Lavandula)

Sedative

Lavender is often used to promote relaxation and relieve stress. Its aroma is thought to have a calming effect on the nervous system, helping to reduce anxiety and improve sleep quality.

Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis)

Sedative

A herb from the mint family is well-known for its pleasant lemony scent and taste. Have mild sedative properties that can help calm the mind and ease tension.

A trial planting session

In May, A/artist organised a trail planting session about making mind gardens. Several A/artist roundtable participants joined the trail. We provided plants from the list above and assigned each participants a big pot to make their try-out gardens. Participants can freely decide selection of plants and layouts in the pot. Throughout the session, we see how gardening brought participants together and created a relaxing and safe environment for people to share thoughts and stories about living with neurodivergence. One participant told us this helped a lot with her social anxiety, as she feels more relived when having something to work on hand while talking with people. It requires less eye contact and provides stimming to reduce her social stress.

Although participants enjoyed the gardening activities and social affinity in the first trail session, it’s hard to see how the initial mind garden concept is communicated through the process and outcomes. As we proposed, the garden as an artistic canvas—an organic space—communicates the diversity of mind through its spatial-sensory experience liberated from labels and stigmas. In other words, the mind garden presents its open interpretation to every individual’s sensory and spatial experiences. Observing, touching, feeding, eating, confessing, hurting…how can we see more about participants' perception and interaction with plants? How to present and document those interactions? What's the human-plant relationship here? Just like the wonderful diversity found within our minds and the constant evolvement and growth of plants, this project is all about embracing discussions and encouraging hands-on explorations on gardening and neurodiversity.

MindGarden - observing how butterflies interact with flowers. Image by Nesie Wang .

Notes

- Stuart-Smith, Sue. The Well Gardened Mind: Rediscovering Nature in the Modern World. William Collins, 2021.

- Scartazza, Andrea, et al. "Caring local biodiversity in a healing garden: Therapeutic benefits in young subjects with autism."Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 47 (2020): 126511.

- Stuart-Smith, Sue. 2021.

-

Schmidt, Dennis J. "Klee’s Gardens." Research in Phenomenology 43.3 (2013): 394-404.