Motor-synesthesia

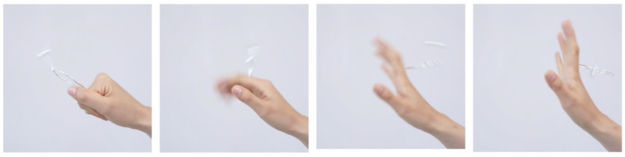

Our speaker Jenny Konrad mentioned that they often think of stimming in terms of synesthesia. “When I hear the word Tuesday, I always see a certain colour“, they shared. “It took me a really long time to realise that not everyone experiences this.“ Stimming movements, for Jenny, work in a similarly intuitive way. “Maybe we can call this motor-synesthesia“, they suggested.

Other people recognised themselves in that word, which started off a discussion about the importance of words and labels to describe experiences.

The importance of words and labels

We discussed that while labels can be used in a discriminating way, they can also be validating and eye-opening, and can help you to find and connect with people who experience similar things.

Weimin Zhu shared how she only found out about the concept of stimming very recently, and how she has since started to look at some of her own habits and those of her family through this lense. We agreed that one of the unintentional consequences of learning a new word could be over-applying it - you start seeing it everywhere. Being overly aware of your own behaviours and those of others in this way can in turn lead to more social awkwardness.

However, Weimin also shared that in her home country, China, most people are not aware of neurodiversity at all. Neurodiverse behaviours are not labeled, but are in turn also not talked about, which often leads to neurodiverse people not receiving the support they need.

Do we need a stimming etiquette?

We noticed that even within our own group, there was still a lot of uncertainty about what “counts“ as stimming, as well as how to act in social situations both as the stimming person and as someone interacting with them. Is there a stimming etiquette?, someone asked. Repetitive movements, especially when they also involve sound, can cause reactions of annoyance from other people in a space. Is the stimming person responsible for explaining themselves? Or should the “stim-tiquette“ instead be for other people to know how to act around someone who is behaving in ways that they may find strange or unconventional? As a rule, people are easily disturbed by any deviations from social norms. “A friend of mine once did a performance which involved walking very slowly in the street“, one of the artists shared. “And someone called the police!“

Could we find ways of saying “Do you mind if I move a bit during our conversation“, instead of masking and repressing stimming behaviours, thereby gently allowing for more freedom? Suppressing these movements, Jenny shared, just leads to other, potentially more harmful ways of stimming, such as for example skin-picking. “Strangely that’s more socially accepted!“, they noticed.

Jenny also shared that for them, stimming is not only a way to deal with stress, but can also show joy or any other intense emotion. “It’s just a way of processing intensity, good or bad!“

Situational stimming

Weimin shared that since knowing about the term stimming, she has noticed things she and her family do in certain situations which reminds her of the concept. For example a repetitive movement during phone calls, or while riding a bike. These things are really situational, she asserted, they have nothing to do with the content of the phone call or the context of the bike ride. “Situational stimming!“, said Jenny.

Is there a threshold for stimming?

This lead us to a discussion about whether or not there is a threshold for what we can and cannot call stimming. Is every repetitive motion a form of stimming? Jenny reflected that it has less to do with a formal threshold and more with why you do a certain movement and what it means to you. “Repetitive motions or sounds can have the same calming effect on everyone, not only autistics“, they continued, “only we need it more because it has a bigger impact on our nervous system.“ Other people pointed out that while the border might actually be fluid, something will commonly receive the label “stimming“ once it is judged not socially acceptable.

Monastery life, again

A theme that surprisingly re-emerged during this discussion was the idea of monastery life being well-suited for autistic people. Weimin suggested that, since monks dedicate their life to wellbeing in a very structured environment, this might be a place where Chinese people who are on the spectrum but lack the words to label and talk about it might feel drawn to. We shared that we have already investigated this topic a little, reading about Hildegard von Bingen in the context of autism and visiting a Dutch former monastery as part of our programme.